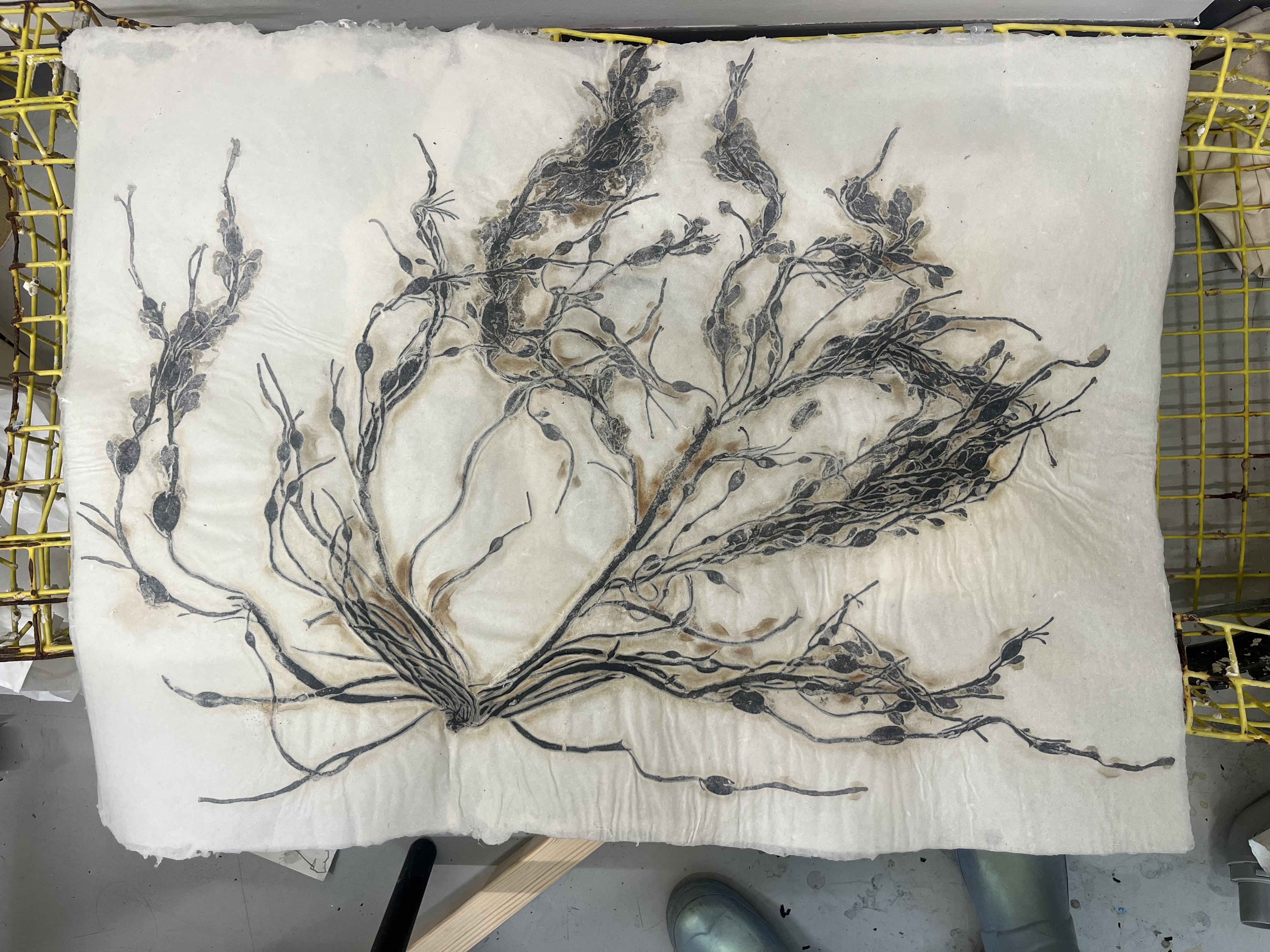

test sheet for membrane: bladderwrack embedded into abaca paper

test sheet for membrane: bladderwrack embedded into abaca paper wood knobs and wires placed inside the lobster trap

wood knobs and wires placed inside the lobster traplobster trap (musical instrument)

2024

1.8 m x 0.4 x 0.3 m

Materials: found ghost lobster trap, 8 hr overbeaten abaca, embedded bladderwrack, ink, goat rawhide, dulcimer strings and knobs, wood

The trap:

Kyle and I walked along the Plum Island shore and found a grid structure on protruding from the sand's surface. We dug it out and discovered a “ghost trap.” A lobster trap that broke free from some fisherman’s buoy liness. The metal object was weathered and warped from its time adrift in the ocean, yet retained many of its original components—a circular netting serving as a "head" for lobsters to enter, two bricks ensuring its sinking, a torn bait bag, and divided compartments within. Only a lone severed crab exoskeleton hinted at its former occupants.

Lobster traps, ubiquitous along the New England coastline, play a vital role in the local fishing industry as an effective requisite for slow and grim death for the crustaceans they ensnare. The captured sea life is extracted from its habitat, maneuvered through the ocean depths, boiled alive, and ultimately consumed.

Working traps represent ingenuity and technology of their crafsman, a sensibility of the encounter between the human and the non-human, and the dispersal of human agency through things. However, “ghost traps” speak more to the agency of the object itself. The ghost trap “frees” itself from the human domain once it escapes the buoy lines. It becomes a part of the shoreline landscape.

The moment we extracted the trap from the landscape we realized we were reinstating human agency onto the thing. This made us concerned with working with the trap as an object which no longer serves humans to predate, but as a requisite for an action that is “freeing”. So we decided to make a music instrument.

The concern also greatly affected the use of organic material as we worked on the trap. Every material that was added to the trap is degradable and if the trap were ever to come into reaction with the ocean water the trap would be dissolved to the original state that it was found in. Instead of engineering the thing to be adept at capturing living things, we reversed the order and trapped the trap with a membrane of cooked bladderwrack embedded into high-shrinkage abaca paper. This material made the resonator. Atop the trap, we placed a goat rawhide for percussion and in the exposed beams we placed wood, music strings, and dulcimer knobs that can be tuned.

We conisdered the possibilities for music to serve as an archival feature of the trap’s materiality and the change it has endured while lost at sea. The architecture of the trap, the bits of remaining sand, the limpets attached to the wires, the netting, and the wire structure, interact with the added material to produce a timbre of the instrument that is made by plucking the strings or touching the membrane of trap. The timbre, or the “color” of the sound, is unique to the ghost trap we found and would be different had the ocean warped the trap differently. Thus the music of the trap expresses the force of the ocean waves that distorded it.

performance at Distler Hall at Tufts University on April 28 2024

![]() bladderwrack paper cast and dried around the trap to form the resonator

bladderwrack paper cast and dried around the trap to form the resonator

![]()

2024

1.8 m x 0.4 x 0.3 m

Materials: found ghost lobster trap, 8 hr overbeaten abaca, embedded bladderwrack, ink, goat rawhide, dulcimer strings and knobs, wood

The trap:

Kyle and I walked along the Plum Island shore and found a grid structure on protruding from the sand's surface. We dug it out and discovered a “ghost trap.” A lobster trap that broke free from some fisherman’s buoy liness. The metal object was weathered and warped from its time adrift in the ocean, yet retained many of its original components—a circular netting serving as a "head" for lobsters to enter, two bricks ensuring its sinking, a torn bait bag, and divided compartments within. Only a lone severed crab exoskeleton hinted at its former occupants.

Lobster traps, ubiquitous along the New England coastline, play a vital role in the local fishing industry as an effective requisite for slow and grim death for the crustaceans they ensnare. The captured sea life is extracted from its habitat, maneuvered through the ocean depths, boiled alive, and ultimately consumed.

Working traps represent ingenuity and technology of their crafsman, a sensibility of the encounter between the human and the non-human, and the dispersal of human agency through things. However, “ghost traps” speak more to the agency of the object itself. The ghost trap “frees” itself from the human domain once it escapes the buoy lines. It becomes a part of the shoreline landscape.

The moment we extracted the trap from the landscape we realized we were reinstating human agency onto the thing. This made us concerned with working with the trap as an object which no longer serves humans to predate, but as a requisite for an action that is “freeing”. So we decided to make a music instrument.

The concern also greatly affected the use of organic material as we worked on the trap. Every material that was added to the trap is degradable and if the trap were ever to come into reaction with the ocean water the trap would be dissolved to the original state that it was found in. Instead of engineering the thing to be adept at capturing living things, we reversed the order and trapped the trap with a membrane of cooked bladderwrack embedded into high-shrinkage abaca paper. This material made the resonator. Atop the trap, we placed a goat rawhide for percussion and in the exposed beams we placed wood, music strings, and dulcimer knobs that can be tuned.

We conisdered the possibilities for music to serve as an archival feature of the trap’s materiality and the change it has endured while lost at sea. The architecture of the trap, the bits of remaining sand, the limpets attached to the wires, the netting, and the wire structure, interact with the added material to produce a timbre of the instrument that is made by plucking the strings or touching the membrane of trap. The timbre, or the “color” of the sound, is unique to the ghost trap we found and would be different had the ocean warped the trap differently. Thus the music of the trap expresses the force of the ocean waves that distorded it.

performance at Distler Hall at Tufts University on April 28 2024

bladderwrack paper cast and dried around the trap to form the resonator

bladderwrack paper cast and dried around the trap to form the resonator